Dr. Stuart Macdonald about his new book, Tradition and Tension

Historian and retired Knox College professor Dr. Stuart Macdonald joins John Borthwick to discuss his book Tradition and Tension: The Presbyterian Church in Canada, 1945–1985. Together they trace the growth, change, and eventual decline of the church through a period of enormous cultural transformation. Dr. Macdonald challenges the myth that this decline is simply cyclical, arguing instead that it reflects a shift unlike anything in history—one that calls for imagination, honesty, and faithfulness beyond institutional survival. The conversation touches on theology, women’s ordination, doctrine, and what it means to live as Christians outside of Christendom.

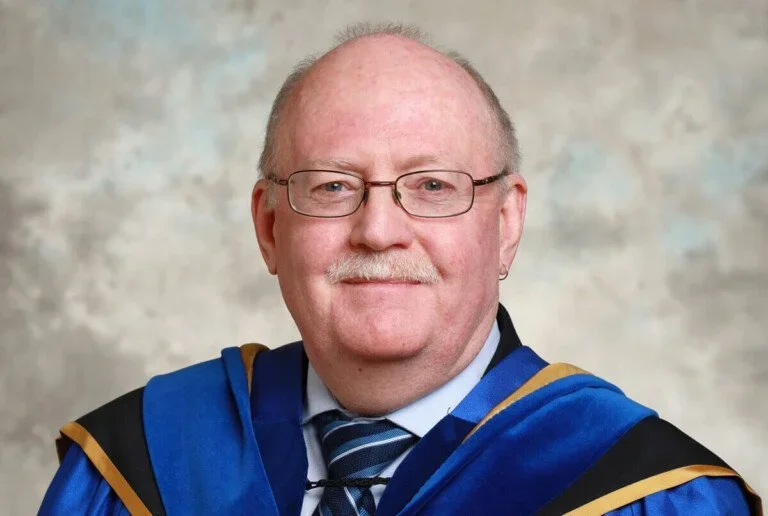

About Dr. Stuart Macdonald

The Rev. Dr. Stuart Macdonald is the now retired professor of Church and Society from Knox College, Toronto. Stuart had been a member of the Knox Faculty since 1996. His research interests and publications are focused on both seventeenth century Scotland and contemporary religion in Canada, in particular religious demography and history related to The Presbyterian Church in Canada.

Stuart’s teaching areas included the global history of Christianity, the reformation era, the history of The Presbyterian Church in Canada, and the various explanations for changes which have occurred related to the place of religion in Western societies.

Show Notes & Additional Resources:

Tradition and Tension: The Presbyterian Church in Canada, 1945 - 1985.

In 1945 the Presbyterian Church was one of Canada’s largest and most culturally influential churches. This impressive standing, in the aftermath of a depression and a global war and just twenty years after much of its membership had departed to form the United Church of Canada, was a mark of the Presbyterian Church’s resilience and resourcefulness. Yet the denomination’s greatest challenges lay in the decades that followed.

Tradition and Tension explores the history of the Presbyterian Church in Canada from 1945 to 1985. In the first half of this period, the church vigorously built new congregations in the suburbs, revitalized existing congregations, and took part in the religious revival of the 1950s. It opened its doors to new ethnic communities, updated its forms of worship, and revised its structures to permit the ordination of women. These renewal efforts were not without controversy within the church, however. Amid the cultural aftershocks of the 1960s, and as membership growth stalled, arguments about who was responsible for the church’s waning influence widened the rift between modernizers and traditionalists. Their common vision was lost.

The place of religion in Canadian society changed dramatically in the postwar period. Tradition and Tension examines how the Presbyterian Church consciously sought to reflect these changes – and how it was transformed and even overwhelmed by them. Get the book here

Leaving Christianity: Changing Allegiances in Canada since 1945 (co-authored withBrian Clarke)

Canadians were once church-goers. During the post-war boom of the 1950s, Canadian churches were vibrant institutions, with attendance rates even higher than in the United States, but the following decade witnessed emptying pews. What happened? In Leaving Christianity Brian Clarke and Stuart Macdonald quantitatively map the nature and extent of Canadians’ disengagement with organized religion and assess the implications for Canadian society and its religious institutions. Drawing on a wide array of national and denominational statistics, they illustrate how the exodus that began with disaffected baby boomers and their parents has become so widespread that religiously unaffiliated Canadians are now the new majority. While the old mainstream Protestant churches have been the hardest hit, the Roman Catholic Church has also experienced a significant decline in numbers, especially in Quebec. Canada’s civil society has historically depended on church members for support, and a massive drift away from churches has profound implications for its future. Leaving Christianity documents the true extent of the decline, the timing of it, and the reasons for this major cultural shift. Get the book here.

Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, 2000 by Robert D. Putnam's

In a groundbreaking book based on vast data, Putnam shows how we have become increasingly disconnected from family, friends, neighbors, and our democratic structures– and how we may reconnect.

Putnam warns that our stock of social capital – the very fabric of our connections with each other, has plummeted, impoverishing our lives and communities.

Putnam draws on evidence including nearly 500,000 interviews over the last quarter century to show that we sign fewer petitions, belong to fewer organizations that meet, know our neighbors less, meet with friends less frequently, and even socialize with our families less often. We’re even bowling alone. More Americans are bowling than ever before, but they are not bowling in leagues. Putnam shows how changes in work, family structure, age, suburban life, television, computers, women’s roles and other factors have contributed to this decline.

America has civicly reinvented itself before — approximately 100 years ago at the turn of the last century. And America can civicly reinvent itself again – find out how and help make it happen at our companion site, BetterTogether.org, an initiative of the Saguaro Seminar on Civic Engagement at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. Get the Book Here

Why Religion Went Obsolete: The Demise of Traditional Faith in America, 2025 by Christian Smith

Proposes that religion has not merely declined but become culturally obsolete

Presents a comprehensive discussion of the qualitative and quantitative forces affecting religion in America

Draws on survey data and hundreds of interviews

Dr. Macdonald also mentioned the work of Dr. Joel Thiessen, Professor of Sociology, Chair of the Social Sciences Department, and Director of the Flourishing Congregations Institute at Ambrose University. If you are interested in this kind of work in Canada, Flourishing Congregations Institute is an excellent source: https://flourishingcongregations.org/

Follow us on Social:

Transcript

[Introduction]

Welcome to the Ministry Forum Podcast coming to you from the Center for Lifelong Learning at Knox College, where we connect, encourage and resource ministry leaders all across Canada as they seek to thrive in their passion to share the gospel. I am your host, The Reverend John Borthwick, Director of the Center and curator of all that is ministryforum.ca. I absolutely love that I get to do what I get to do, and most of all that, I get to share it all with all of you. So thanks for taking the time out of your day to give us a listen. Whether you're a seasoned ministry leader or just beginning your journey, this podcast is made with you in mind

Ministry Forum podcast listeners, we are back with a returning guest, The Reverend, Dr Stuart McDonald, transfigured by retirement. We're here to talk about his newest book, Tradition and Tension the Presbyterian Church in Canada, 1945 to 1985. I'm confident this book, like Moir’s Enduring Witness, will become required reading for future PCC students. I'd make the case that if you're in ministry today, in whatever iteration that might be, either clergy or lay, this book is a must read, even if you aren't Presbyterian, because sometimes it's a little easier to look in on another denominational flavor to hear what you need to hear, perhaps for your own context. You are actually our second history professor we've interviewed for the Ministry Forum podcast recently. It is in post-production right now for a future release. But a few weeks ago, we had the pleasure of interviewing Dr James Tyler, Robertson from Tyndale seminary, and author of Overlooked, the Forgotten Origin Stories of Canadian Christianity. For this history lover, it's been delightful, and James was made a few comments about you, and they were all very positive, Stuart, as far as I know, so you can get a dig in game is a good friend. Yeah, a good man. All right. Well, let's get to the bio the Reverend, Dr Stuart McDonald is the now retired Professor of Church and Society from Knox College Toronto. Stuart had been a member of the Knox College faculty since 1996 His research interests and publications are focused on both 17th Century Scotland and contemporary religion in Canada, in particular, religious demography and history related to the Presbyterian Church in Canada. Stuart's teaching areas included the global history of Christianity, the Reformation era, the history of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, and the various explanations for changes which have occurred related to the place of religion in Western societies. Great to have you in our virtual studio today.

[John Borthwick]

Stuart, welcome.

[Stuart MacDonald]

hank you very much.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, well, maybe let's start with a little more about you. I've shared your bio. It's a little more robust than what appears in the back of your book. Let's talk about humble but is there more to say about Stuart? What would you add to your introduction for our audience? How are the first few bites of retirement?

[Stuart Macdonald]

I think the introduction is great. I think work stands on its own. I mean, I've been writing history for decades now. I hate to say and teaching it and in loving all of that. So that's been great retirement. I'm keeping really busy. I still haven't figured it all out, as you know, and others may know, I have a lot of interests, and so it's just been fun. I've been playing guitar a little bit more than I have been. I'm continuing to teach myself how to play gospel organ, which is something I'm not even a pianist, it's just a lot of fun. And I love to hike, and my wife Gail likes to hike as well. So we've just come back from doing the last section of the Portuguese Camino to Santiago de Compostela. So that was really wonderful. So I'm still trying to figure out retirement. I'm keeping busy. I'm enjoying things. I'm also enjoying being able to go down and build Lego with my grandson. And that's so it's, it's all, all very enjoyable at the moment.

[John Borthwick]

That's wonderful. I'm glad you're having a good time. And now you are a pilgrim, I suppose, of the Compostela, yes. Well done. Well done. I'm sure there's some elitism about well you only did a few days, not the whole thing, and you have to take, like, years off to walk from who knows where to who knows where, but well done. Good for you. Yeah. On the Ministry Forum Podcast, we like to encourage people to read the books that authors that we interview have shared with us that's kind of my process. I always read a book before I have a chat with an author. So our conversation, as much as we're encouraging people to read the book for themselves, our conversations are really about what kind of stood out for me, and you can see but maybe not the visuals here, I like to put a lot of little notes and flags and books as I read them, and so I've got a bunch in your book. I found it quite intriguing, and probably because it's the home team and all that kind of stuff, I could see some stuff. So let me start with this one, and I apologize for the long preamble and this one, what really stood out for me personally was how many of the names and places that I recognized now, again, it's home team, either connected to my own congregational ministry journey, or just characters of significance who are still remembered in the church today. It was kind of a nostalgic ride, noting legacy after legacy, and I guess that's what history sometimes is, write it from the opening paragraph of the introduction, where you mentioned Dr Finley G Stewart, a name that gets mentioned to this day at St Andrews Kitchener, whenever I've turned up there, even just a few months ago, someone even suggested that I I think it's because I'm a white guy, an aging white guy that I reminded them of Finley Stewart. They were there when Finley was there, but these are, he shared some things on the occasion of our centennial in 1975 that the year would be a test of our worthiness in this generation. And then Dr William Stanford Reed's name is peppered throughout this book as an influence on the denomination felt for many, many years in a variety of different ways in our history, when I arrived at St Andrews Guelph in the early 2000s I only heard of his antics, I'll call them from some of our parishioners. He certainly was one of those characters in the church, who was known for his running commentary during worship services in his later years, and your description of the expansion and growth of our denomination, specifically in the press tree of West Toronto, where I served at Rexdale upon graduation from Knox College. You even have a nice little picture of the portable sanctuary they were using as they built their building project in the 1950s and the establishment of the congregation of Westminster St Paul's in Guelph in 1958 who ended up amalgamating with Knox and St Andrews Guelph in 2022 just before I left St Andrews for this role at the College and Hopedale in Oakville is mentioned, where I served as an intern during my studies at Knox College, who have recently amalgamated with Knox Oakville. I'm starting to notice a bit of a pattern here, and maybe that's one that comes with advancing years. So if you'll excuse this long preamble, I came to observe that over the span of 65 to 75 years after the end of World War Two, all this expansion is now changing, shrinking, maybe even contracting and disappearing. All of the legends of old are perhaps dead and gone, and many of the churches that were brand spanking new in the 1950s have probably closed or amalgamated, or are thinking of doing so in the next few years, and I, and many of my colleagues in congregational ministry, are the witnesses of this erasure. It felt a bit like a big crunch theory of the universe, which has been disproved. Listeners, apparently, scientists say you need to go and do your own research, but scientists say the Big Crunch theory is not a thing, but it's like we had this big bang of like explosion of growth, and now it's all suddenly come back into its original state, shedding much of the growth that it experienced. It feels like a natural thing, like the circle of life. But I'm wondering, is this a common experience in history? Or how would you comment on this observation? I've often heard you say, just like we've had no control over the expansion and contraction of the universe, that what has happened to us over the last two generations really isn't our fault, necessarily. Thoughts on this, Stuart.

[Stuart Macdonald]

Well, thanks, John. Some great comments, and I'm glad you read the book and made notes and enjoyed it, and I'm glad that it connected, and I hope it does the same for others in terms of some familiar voices, some names. I didn't want to be just a list of names. There's a reason those names are there. I think some of the things they say are profound, and I learned so much from those different voices. But I'm glad the book connected, I really am, and my hope is that it connects with others as well. Let's start with the it isn't our fault comment, which I think is, is great, and it's very true. I often say that, and I usually say it following some other comments. So just to bring those comments in. And to other people noting that this, what we've seen, has been a result of an external change, a change in the outside culture. So it's not, as is so often argued in the church, by something internal, by something the church did, a wrong theology, a wrong program. When we continue to have that debate, we will continue to have that debate, unfortunately, but really, there was an external change in this period, and I know we will come back to that. So this period from 1945 to 1985 was a key period, and it was very carefully chosen. It is a hinge where, as you've noted, we moved from growth to something different, and by 1985 we've got decline. It's not as extensive and as obvious as it is. Now when you look at the graphs in the book, we tried to keep those to a minimum, but you can see it just continues in this way. One of the things I want to say, and again, this is something that we do hear people say that this is all part of a cycle, or there's it, this always happens. And there's a particular strain of thinking in United States, in sociology, or pop sociology, that has everything in cycles and generations and patterns. And I just want to say, no, absolutely not. This is something new that has never been experienced before, and I know how terrifying it is to start to come to terms with that. I appreciate that. And one of the things that we see change over these 40 years, not just in the Presbyterian Church in Canada, but well illustrated within the Presbyterian Church in Canada, is we see less participation, attendance. We see less identity or affiliation. If we go beyond the PCC, fewer and fewer people are telling the census that they have a particular Christian religious denomination. So both of those things were covered in Brian Clarke and my book, leaving Christianity, and that's really what those involved. But with that, we also had less cultural support. The culture wasn't looking to the church to provide answers, not the way it was during World War Two. It's hard to imagine the prime minister in 1985 having a meeting with church leaders the way that it happened during the war. So you have less cultural support, you have less political support. So I'm not aware we've ever had that combination before. And it's that cumulative effect that I think really provides something new. And so I really, as you can hear, strongly reject voices saying, Oh, we've seen this before, or it's all part of a natural cycle. Now, there are some elements that may have some similarities, maybe. But when people just throw, oh, we've seen this all before, I want to stop, and I want to ask, what data do you have for that? What? What are you going on to make that case? And we often aren't even allowed the opportunity to do that. And I've since leaving Christianity came out, Brian and I have each, individually and collectively, had some experiences of of people saying, Oh, we've seen it before, or denial of the basic theme of that book. What I think tradition intention does is tradition intention illustrates what we found in the numbers on the ground, in the church, and so I think it really builds on that in a really important way. We are not going back. This is something new, and we have to do something new, if we want to take anything out of the book and build on it. But from a sheer historian's point of view, this is a shift at a key moment when Canadian culture moves out of Christendom. What does it. Look like on the ground in one denomination, and that's the story the book tries to tell. Yeah.

[John Borthwick]

And I think I hear in that a comment that you make in the introduction, this idea of we need to know what happened and what was done before we judge too quickly what went wrong. Yes, we need to know the facts first. You say, Aren't facts fascinating? No, you say the facts are fascinating, at times supporting our pre preconceived notions and other times challenging them. And so it's certainly a sense of as I read the book and as I as I reflect on my own ministry, I feel that much of my ministry was about dispelling myths related to our denominational history or even the current circumstances we find ourselves in. People would with a nostalgic looking back, would sort of would make comments about the way it was, and even in my own in my own context, when you serve in one place for a really long time. I had served for 21 years, even when people would say the typical traditional church comment of we used to do this. And it's an incredible position of power to be in when you've been there for 20 years and go used to do we've never done it in my 20 years. So let's just start there. We're at least 20 years out from when we used to do something. So I think it's, you know, it's human nature. It's just who we are as people. Sometimes we use it to tell our stories as a kind of suggesting our own rightness, or pointing at something and saying that's, that's whose fault it is, or blaming I wonder, as I read the book, there was this book had sort of a disciplined practice of just the facts, ma'am or sir. Has that been part of your experiences in long service as a steward and interpreter of our PCC heritage?

[Stuart Macdonald]

It absolutely has been - we have a mythology, and we're not that different from other organizations. And so I just have to say, I learned a lot in researching this book, a lot that I didn't know, and even in some of the choices of pictures I wanted to share with people, some of the stuff they never even imagined, like a Christian rock band, and when it was, it was that early, and just so there's a lot of that I, as I said, learned so much the origins of this book, as I think I said, really came out of teaching. And one of the early origins of it was trying to say, how did we build new churches? And one of my students asked a question. Went off to do that. Now, the book got parked for years because until the deeper background work was done, and that's what my colleague and friend Brian Clarke and I did, my co-author on that book. We wrote that book together in Leaving Christianity until we did that, the rest of it made no sense. And so, but while that was going on, I was still teaching. And so all of a sudden I had to talk about this and talk about this and talk about this. So when I came back, what I thought originally would just be a book about church extension, it got changed. It's what are the things we don't know? And so one other simple example, theology. So why did it take the Presbyterian Church in Canada so long to get a contemporary statement of faith, living faith? I didn't know the answer. Everyone just said, Oh, it took us so long. So why another thing worship? What about the Book of Common order. By the time I was graduating in seminary, that's a long time ago, we had the abbreviated version. I'd never even looked at the original, and some of the things I was told weren't quite true. So yeah, it was a fun exploration. I tried not to make it just, oh, we got this wrong, but just to say this is what happened, and I think it's a much richer story than some of our inaccurate preconceptions.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, I think there's, that's always the way, isn't there? There's these stories we tell ourselves about how things work or how the how things came to be, but then if we actually do the history and the actual data and actually go back to the original evidence, we go, oh, wait a minute, that's not actually true at all. I wonder if one of these is similar to one of your chapters that's devoted to the changing place of women. I so appreciated your detailed take on that part of our history and and certainly people need to need to read it for themselves, but I wondered if you would tease out for our listeners appetites by speaking to the cautionary tale, if you will, as it relates to this misunderstanding, especially related to. Liberty of conscience, a recent conversation point within our denomination. I'd love for our listeners to hear just a teaser of what some of that might be related to.

[Stuart Macdonald]

Yeah, thanks that. That was, that was a fun chapter. Actually, that's two chapters that, you know, it's a theme, and we divide it into the two chapters. But it was, it was fun to write, and I learned so much. And by the very end of the book, just as we were going to press, I discovered something new. Had I known that earlier, I would have written it even more assertively in a few places, but it just was fascinating. So let me begin and say something that just needs to be said, that liberty of conscience, as traditionally understood, had and has no place in the discussion of how the Presbyterian Church in Canada made their decision on the place of women in the church. So liberty of conscience should not be as we've traditionally understood it. Part of the discussion on the place of women in the church and how we've traditionally understood it, which I explored in the book, is we agreed beforehand that we're going to disagree on this. But that isn't at all what happened. So what happened? And as you know, there is a lot on this in the book, and lots of details and some twists and turns, but basically, in 1953 the there's an overture from the Synod of Manitoba that asks us to look at the place of women in the church. The word ordination isn't used, but if women are going to have a voice in church courts, where everybody has to be ordained, have to talk about ordination. They knew that we did the typical Presbyterian thing. We created a committee. They polled the church, a lot of straw polls, all of that kind of thing that develops, and so they begin to explore this question. One of the key moments was the publication of a Bible study for the denomination to use by the committee that was looking at this. And the committee the Bible study is called putting woman in her place. And they meant that positively. I know that we might not think of it that way, but that's what they wrote. They created a study guide, and the book actually goes into some detail on that, because people have it. And I think it's just important to see that the church made this decision through a careful theological and biblical study of the texts and the church from the day that committee was founded. They realize there are different texts in Scripture, and they it's a very wise committee, and they say, We just can't have one voice overriding everything else. We've got to figure this out now, as we'll discover, or you'll discover, as you read, there's still those people who say, No, this verse trumps everything. But the denomination as a whole said, No, we're going to look at the entire witness of Scripture. And that's what they did. They published that in the church. And you can see, I think, that that really changes minds. And so in 1965 a motion is passed to allow women to be ordained as elders and ministers. And that passes the 1965 general assembly, but no controversy, and it is sent down under the barrier Act. Now, the barrier Act is a major character in the book, because some of our key decisions are made around it. And if we don't understand it, we don't figure we really don't know why the denomination is doing things. They are there so they're doing everything proper. 1966 the votes come back. The majority of presbyteries, representing the majority of Presbyterians, approve of the ordination of women as both elders and ministers in 1966 then the General Assembly does the third step in the process, and they pass it. Now there is more controversy there, but if you've been around the church long enough, you know that sometimes your position doesn't win, and that's fine. That's part of the that's part of who we are. And so as of 1966 what happens is women are allowed. Be elders and ministers that is part of church doctrine for Canadian Presbyterians, that is part of church law, and there is no way around that. And it's actually even published in the book of forms as who we are. That's something I didn't know. And so it's really upfront, this is who we are. Now the immediate impact of that is, all of a sudden we have women on sessions, and by the next general assembly, we have two women commissioners, which is the first time we've had women commissioners at the General Assembly. So I think the immediate impact is on sessions and general assembly and women finally have a voice in the courts of the church, given all the work that they have done, seems to me only natural, and the church decided that this was appropriate, and this is what Scripture and our theology said was appropriate. Now, when we've often told the story, we focused only on ministers, so I really wanted in the book to talk about the importance of elders, and we do get a few gifted, exceptional women who feel strongly called to be ministers. And these individuals go through and that's great, and they actually become ministers of Word and Sacrament, which I think is is fantastic. And they face some barriers and just talk about what that looked like a little bit somebody else. I think now that this book is out, can go in and perhaps interview some of those people and talk even more about that. But this is all the church has decided. This all is good until 1979 now, one of the things that's happening is some people don't agree with this, and what happens is, as more and more women move into ministry, their resistance, defiance, you choose the word becomes clear, and it's including People with key roles in the church, including the mission superintendents, and at that point, were responsible for appointing people to their first charges. And in 1979 it comes to light that there is active discrimination against women, that the mission superintendents are actually defying what the church has said and said, No, that congregation doesn't want a woman minister, and that's okay. Whoa. In popular memory, though that's not what we remember. And I would like to credit Joanne Dixon, who graduated from Knox for doing some of the initial work on this, and it just, I really appreciate what she did, and I've done my own work and built on that, but we don't remember that. Instead, a novel and audacious claim that it was okay to be a minister of the church and disagree with this position, but only this one. It's a doctrinal position, and a position on our polity is advanced, and it just creates controversy. And that's why, and I struggle to even say that this new, this novel, this way of understanding that I get to choose, as a minister, which doctrines I have support is proposed, and a lot of people agree with it. And so we get into what ends up being called the liberty of conscience debate, but it's a really a hijacking of what was going on, and we've forgotten that what triggered it was the church got caught actively discriminating against women, and I think it's really unfortunate. So the book goes into a lot of detail, but I just want to say this has nothing to do with how we've traditionally understood that term liberty of conscience, where we agree beforehand, before, or how we are now using it. This is something different entirely, and I think it's just important to do that. And if people want to go back and read the task force report on it. I think it's good. So a lot of detail in the book, because I think it really is an important and frequently misunderstood issue.

[John Borthwick]

For sure, Stuart for sure, and it speaks to, I think, a number of things, and something we're going to get into in just a sec. But just this notion that as leaders in the church, ministry leaders, whether you're an elder or a teaching elder or a ruling elder, a minister or lay person, especially when you're in a leadership role, how we treat doctrine, you know, is, is it choose your own adventure? And something we're going to get into just now, maybe it speaks into that. So here's the thing. So what I found fascinating, certainly the what you've just described, but another area of debate and engagement in the church during the period that you're looking at was around confessional statements, the development of the declaration of faith concerning church and nation. And as a now retired Minister member of the faculty of Knox College, I wonder if I could invite you to react and or comment on this musing of mine. I was recently at a service of ordination and reminiscing about the number, number of times that even as a moderator of a presbytery, I've read out the preamble as outlined in the service. I wonder if we had a body language expert at such an occasion, if they might pick up on the ordinance tells upon hearing the words, all of these things you have examined and are ready to accept. And questions come to my mind, have they? When did they? Is an examination of the Westminster Confession of Faith, the declaration of faith concerning church and nation and living faith, a part of the MDiv curriculum. You can speak to that in a second. I don't feel like it was when I went to Knox, not in a fulsome way, and certainly before the World Wide Web was actually made public when I went to school in the olden days. And a really interesting side note, not to trigger people, but it's interesting, the Presbyterian Church in Canada's website doesn't include the declaration of faith concerning church and nation as one of our foundational documents. Just by a title on the website, it says foundational documents. It includes living faith, the Westminster Confession, but it also includes the shorter and larger catechisms, but misses the declaration now, after years of time and energy that was spent seeking to articulate our faith. It's just fascinating to me that people spend all this time on it, and yet I wonder how much time the average seminary student or the average person who's discerning a call into being a ruling elder in a congregation in the Presbyterian Church in Canada? What say you? Dr. McDonald, what to this? This, this musing.

[Stuart Macdonald]

I think the musing is largely accurate and without I think what is fascinating about theological curriculums, because I've experienced this at Knox, is you have it in one course, and somebody else discovers that somebody's teaching it, and they take it out of their course, and the other person drops it, and all of a sudden it isn't there. So I think there are honest keeping curriculums aligned to teach everything is always a challenge. However, I think it's something the colleges all three need to do. And I think I've often wondered, I think the preamble at ordinations is simply brilliant, and I've often wondered if it should be part of the either the licensing of a minister or probably using the old term, but part of the presbytery process, or part of the college process that you have to actually be able to understand and explain those documents, all of them in terms of what they mean. I think that would be a really good thing, but I think the colleges have to do better. I would agree. I also think the denomination needs to do better. And I think you've pointed out a really interesting example, and there's been other times where it's been other things. I remember when I was being ordained, I went up and I was given a gift certificate, so I was at the Presbyterian book room, it went through a lot of iterations before we got rid of it, not got rid of it, is an unfortunate way to say it. We all know how bookstores are just challenging now, but it went through some different ones. This wasn't one of its high points. So I went to buy a copy of the Westminster Confession, and discovered I ended up with the American document, which is significantly different, and if nothing else, I learned that, which was a good thing. But no, I think, and even moving forward, John, I think one of the treasures of this denomination are some of those things in its heritage. And I would particularly want to stress. What a great document. I think living faith is. I think if there's a grief in the book, for me, it's that that came so late. And I just want to honor Stephen Hayes's work for a personal friend and a mentor. But as I read that, every time I just go, Stephen, you are so brilliant. In particular. One of the things that John, you may have noted is there were times before where the committee would get bogged down with somebody not liking something and to try to appease the entire church go in a different direction. And so on, the committee that came up with living faith realized they weren't going to get 100% and they were okay with that. And I just think that's genius, and I but I do think we need to stay with who we are, more than for whatever series of reasons we've moved away from it. And one starting point would be just students knowing what are all the things that are key, and they're all in that preamble, all of them,

[John Borthwick]

For sure, Stuart, it's often interesting. Where it comes out most clearly is that general assemblies, when someone deigns to speak and go to the mic, and I'm sure I've done the same over the years, but yeah, I can remember leaning into somebody occasionally. And this is not about digs against theological seminaries, but it is one of those things, perhaps about just the process in its entirety, where I've leaned into somebody and went, did that person just essentially speak heresy, or do they understand a certain doctrine that we're supposed to affirm? I don't know what they're saying right now. This is very confusing. But yeah, there's, there's this notion of, and this is probably, I'm going to go off, go off script for a second in the sense of thinking. What comes to mind is this is probably where the, I think the beauty of the PCC, where there is such diversity in even theological sort of thinking and such and a free thinking, in some ways, like to question and wonder and have that kind of experience. But it's also where you could experience doctrinally, which is, I'm going to say that in certain circles of the PCC, as I've experienced it, don't speak a lot of language around doctrine in the same way, but, but where orthodoxy and doctrine doctrinal ways of thinking are like, Well, sure, you can have wonderings and thoughts about this, but you need to know that the PCCs doctrine on this is clear, just like what we were talking about in the previous thing, the doctrine of the Church, it isn't something that we just sort of had a decision on, and it's, you know, sort of there. It's like we've decided the doctrine of the Church is that women will serve, can be ordained to serve as ruling or teaching elders. That's not just, oh, that's a nice to do. It's doctrine. And so

[Stuart Macdonald]

It's, yeah, it's not debatable. And let me say another thing, one of the things that we say, and I would, so I'm agreeing with you 100% that there are, there are these boundaries, and if you start to move outside those boundaries, one needs to think about, is this the right denomination? And we have been very inclusive, and I honor that, one of the things that we say is scripture is authoritative, and we define that in both living faith, which I think is brilliant on scripture, and a very different take in the Westminster Confession. One of the challenges the PCC has, and I don't want to go down this rabbit hole, but is to have having those two different documents. What I found interesting the last few years is on one issue, somebody will cite the Westminster, but not living faith. And so I think we've created a little bit of a problem. I think we could solve it, but the whole impetus to actually have standards and to say this is who we are, I think is, really significant. I, for example, continue to believe in {presbyteries, in our collective wisdom, as much as it strains me. At times, I do believe in that. And so that makes me different from someone who would believe in one person, or this is starting to become more relevant, and where you have the monarch telling the church what to do, and we can just let that hang. But I think. That's really interesting, because one of the things we've said as a church is, no, the church speaks. And so I agree with you. I think we have to recognize where our boundaries are and respectfully say to each other, if you no longer believe this, maybe there is, and there is. There are lots of them, other places within the Christendom that you can find a church. But we believe in this. We believe in Bible as authoritative, but bible where we read it as a whole, we don't just pick up a Bible verse here and beat each other to death with it.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, maybe, maybe on this topic in particular, it's that notion of the dialogical nature of Scripture, but also the diagnostic dialogical nature of confessional statements. Absolutely, you know, there's a sense that Living Faith isn't in opposition necessarily to the Westminster Confession, but the two documents are in in dialog, discerning historical, you know, as they've moved through history, there's a sense of, you know, so, yeah, it's an interesting, interesting place. I was really intrigued, probably because of my oppositional defiance disorder. Or I like to think of it as a, you know, a kind of charism showing the Congress of concern of 1968 Yes, this sound. This sounds like a fun little group of people. Stuart Coles was a part of it, who I've had, I've had the pleasure of intersecting with in a couple of interesting occasions over my lifetime. Can you tell us a little bit more about this this time in our history? You don't necessarily have to answer this question. But do you think it's time for another revolution of some kind, another you know, Congress of something.

[Stuart Macdonald]

Yeah, the book went into the Congress of concern, and there was so much that got ended up being cut from it. I ended up writing another article on it. And there are a few places in the book where, and I want to just honor my publisher, McGill Queens, is just been fabulous, fabulous to deal with all of the stuff. Just great, but they had a word limit, and that's so there's things that got cut. I think the Congress of concern is fascinating, but so is the 67 Congress. So is the lamp report, which nobody talks about. So is the Ross report, which nobody talks about. And so is the 1971 the first report on church decline. So just think about that. In that brief period between 1967 and 1971 there were two congresses and three major reports in the history of the denomination. So that's a really rich, crucial time in our denomination. And I see, think what we see there is a very real attempt to what was understood, to respond to what was understood as changing times. Now, one thing I want to point out is none of these reports were data driven or the congresses, even when they use numbers, they use numbers, but the numbers and what they're saying don't always line up. It really is interesting. People preconceptions drove all of these reports. The Ross report most grievously, I think. But I can say, and I do say in the book, a few things about the 1971 report as well. I think another thing that's interesting is all the reports focused on institutional issues, the shape of the denomination, programs, those kinds of things, not deeper issues of faith, and whether we were connecting with society, even the Congress of concern, I think we could, could talk about that that way. And they were two basic diagnoses, and they the ones we still hear. The one was the church was in trouble because it wasn't relevant enough. The other is, the church had given into culture too much, and people were leaving because we'd abandoned the orthodoxies of faith. And we hear both of those to this day. So I think it's it's a fun period to look at and just to see the origins of our discontent, and the fact that even back then, you had those very different views. One of the things I kind of suggest, it's in the background of the book John. But. I want to highlight it. I can't prove it, but I want to highlight it that I think those groups within the church started to identify with external groups to the denomination communities that had a similar ilk, and so that Presbyterians who were more ecumenical, look to the world. Council of Churches. Presbyterians were more evangelical. Look to evangelical organizations. So there's no longer working within the denomination. We're starting to speak to external constituencies and listen to those voices. I'm not sure I can prove that, but you'll see me hinting at it strongly in the book, and I'm acknowledging that I'm on thinner ice there than on most places where the information is really solid evidence. I think for what I'm trying to argue doesn't mean you can't argue against it, but there's pretty solid evidence. Now, if we're going to have a revolution, I'm okay with that, but I think we need to do it differently, and the two things I think we need to do are look at the data, and second is focus on the key issues, which are issues of faith, not just institutional issues. The lamp report spent so much time, or at least the legacy of the lamp report, is figuring out how to have people have voices in the church, and they ended up creating a monster. You had all these committees, and all people were doing was going to meetings, and for those of us who inherited churches that did parts of that, it wasn't what we should have done. We should have focused on education, building a more informed laity who understood what the Christian faith was and how we as Presbyterians understood that Christian faith, that's my soapbox.

[John Borthwick]

I love that soapbox. It's a great one. I've stood in it myself occasionally as well. And I will confess that when I started in my first charge, within the first year, I found the lamp report, or discovered it or reinvented it, because they had no committees in the first church I served, and I I confess, and I'm sorry for those good people at Rexdale that I encouraged them to have multiple committees as structured by the lamp report as the denomination had from on high delivered to us all as the commandments of how we do committee work. And then to punish me, I assume that the God of my understanding sent me to a new church where they had 15 committees when I started there, and I worked my way through over 21 years to get them down to like, I think, three or four, some by attrition. I mean, they just ended, but 15 committees there was in my first couple of years there, true, and I tried to have them meet on the same nights and all that kind of stuff. And truly, there I could be out at least 10, sometimes 15 times in a month just to be in these meetings with all these various and disparate committees. So it's a thing we love to do structure.

[Stuart Macdonald]

We love structure, and sometimes to solve one problem, which was too much centralization, we create another problem. And that's human nature. I just think we need to acknowledge.

[John Borthwick]

For sure. So the book does demonstrate the path of decline that we have been experiencing since our peak in the mid 1960s and a variety of attempts to get us back on an upward trajectory, I suppose. So let's give the people what they want. Stuart in a nutshell, when did the decline start? Why did it happen? And is it our fault? Or maybe a better question, why didn't our attempts to use your phrase to staunch the bleeding work?

[Stuart Macdonald]

Yeah, let's begin at the beginning with that. So what happened? The key answer is that there was a cultural change in the 1960s that cultural change is still being fought over in our culture. Now, I just want to emphasize that even our culture doesn't agree on it. It's moved in some other places, but it was a change in the culture that had a profound impact on the church. One way, one short way of thinking about this is we moved from being focused on community and community approval and respectability to. To individualism and self fulfillment. So that's short form. People can think a lot more about that. Brief aside. This was the first cultural change. I think we've had two more since then. I'm going to say a little bit more about that in just a second. But this cultural change affected institutions that had previously thrived, and I continue to just recommend to people read Robert Putnam's Bowling Alone. It's an old book, but it's brilliant. Its weakest chapter is on the one on religion. But even there, it's still a great book, and it's just important to recognize the lodges, the Masons, the Odd Fellows, they went through the same thing. Service clubs have had a slower trajectory. So there's something in an institutional form that gets rejected in this period. So that's again, an outside cultural change. The churches absolutely were affected by this, and tradition and tension really tells the story of what this looks like. And I've already noted that it's really putting stories and examples together to illustrate what Brian Clarke and I had already noted the numbers showed. So the two books are very much in alignment. And I just, I think that that's this book puts flesh onto the numerical bones that Brian and I put together. And so the insights of Calum Brown and Hugh McLeod, people who've seen the 1960s cultural change is significant. Those are still the voices I think we really need to look at very briefly. Why did none of our attempts to deal with it get to it? I think it's because we weren't data driven. Sorry, we published all these numbers, but we really didn't look at them seriously. And so that's the scientist part of me, the fact based part of me being highly critical, and I want to recognize that it's easier to see it from distance. I'm more worried about why we have not. I can be more forgiving of the people in the 1985 than I can be at people in 2015 or even 220 20 or today. I think the evidence of this is really clear. And I think and the work of other Canadian religious sociologists, colleagues and friends that I just respect so much has just shown that this is real. And I think denial, denial, denial continues to be how not only the Presbyterian Church in Canada, but many others continue. If only we did this little tweak, we'll get by. Which, forgive me, I'm now going to talk about what I think is going to be, where we're going to go to ignore the reality for the next little bit, which is I mentioned that this is the first of three cultural changes. And I think Christian Smith in his book that came out recently why religion went obsolete, I think that's a great, important book. I think it brilliantly explores that second cultural change and helps us to see what went on. I really want to think that. I don't think he separates out what enough. This is a general criticism of a fine book, what I would call the third cultural change, which is the impact of smartphones. What a horrible name and the pandemic, the covid 19 pandemic, I think that's not just accelerated, that those things are even cumulatively different. The point is, and Smith would argue this, and I would argue this, the church is not built for any of these things, and it doesn't speak into the culture. And so if there's a challenge for us, it's how to speak into the first cultural change and the second and the third. And what we don't realize is that our denomination, in its institutional structures, is built to speak to a culture that started to change in 1958 so. Afterwards, and we did well for a while, but we really haven't come to terms with that, let alone the later changes. So that's why I think, that's what I think has happened, and I still don't see us having those conversations. I think we are interested in preserving the institution, and we have a failure of imagination to figure out how we can live as Christians outside of Christendom, and how we can live as Christians outside of the form of a congregation that has existed for only about 200 years, our congregations that we imagine with groups and this structure and that structure and buildings in the way they do doing the things that they do, those are only about 200 years old. What did Christians do for 1800 years? Maybe we could start thinking about that. I think one of the reasons that pilgrimage is taking off is because that's an older way that people find meaning a time outside now, a lot of secular, quote, unquote, secular people find meaning in that too. And I would say that that was very clear when Gail and I were in in Portugal, but, but you don't also want to judge why people are there, but, but that idea of time out, of time aside, a special time to grow in Faith. What about that? What about other things? And this, John is where I think we have a failure of imagination. How do we live as Christians if we don't have a Christian government? South of the border, there is a significant number of people who have said, you can't, and therefore we're going to make the government Christian, quote, unquote Christian, but in an understanding of Christianity that many of us cannot recognize as having anything to do with Jesus. And so we're at a very interesting moment in time, but that's my attempt at an answer of why the culture that the church was built for change. We kept doing things and we kept doing them faster and harder. But that doesn't work. You have to do different, and we haven't

[John Borthwick]

Really amazing insights Stuart as we draw our conversations are close. I'd love I just as I was listening to I just love to have an extended podcast where you just basically riff on history in the present day, just freely knowing your musical background. We could call it stew unplugged. And I know I'm not supposed to, I'm not supposed to ask historians to predict the future and hear me say ministry forum. Audience, I don't mean this as a criticism of the current work of the denomination in supporting the special commission re hope and possibilities, I have the utmost respect for all the good people who've been involved in the back behind the scenes and who are now have been commissioned for this work, but, and yes, I know that potentially means a dismissal of everything I've just shared, but, but as I read your book, Stuart, I couldn't help but see all the human efforts at pulling all the levers and pressing all the buttons and working harder, like you've said, from the 1950s all the way up into the 1980s and I just wondered, Are we destined to repeat history again? Is the Champagne Supernova? Shout out to Oasis of the PCC, a natural progression of time and trends, and even beyond the PCC, the mainline church in general? What do you think?

[Stuart Macdonald]

I think our destiny is in our own hands. We just have to grab it. And I think that's where the challenge is. And I think so go sideways for a second. I know when I'm working with students, graduate students, when I'm working with MDiv students, when I'm working with people I know who are struggling with an issue, when I'm working with myself and something just isn't working. I have a really simple formula, which is, go back to the basics. What is it you're trying to do? Just go back to the basics. What's this all about? So if it's an essay, what are you trying to say? If it's thesis, what's your argument? If it's a sermon and it's gone off the rails, Macdonald, What do you think you're trying to tell people? What do you want them to do? So, John, it's the simplest thing possible, but I have found it. I have to keep relearning it. I think what the denomination needs to do is focus on focus on faith, not institutions, focus on what it means to follow Jesus. Who do we understand Jesus to be? How do we walk as his disciples? That simple, the three things. And I've been saying this for so many years, I'm almost embarrassed, but I can't change it. There's three things I think we need to focus on - worship, education and evangelism. And for people who aren't comfortable with evangelism, passing on the faith or sharing the faith, we have no trouble telling people why they should watch this TV show, telling this people, why should they watch this movie? Why, as followers of Jesus? Do we struggle to say respectfully, not telling people if they disagree with us, they're going to burn in hell for all time? I think God is more gracious than that. That's my theology. I think God chooses that's one of the things I take from the Westminster Confession. It's probably not a quite great reading of it. But who knows. I think it's a good reading of Scripture anyway. As our colleague, retired professor Nam Soong said, evangelism is telling people why living with Jesus is better than living without Jesus. We just need to do those things, and we need to do them unashamedly. We need to do them graciously. If we're not sure what we understand the Bible to mean, we need to go back to the main teachings of Jesus. And so I think that, for me, is really what's central. We seem to be more concerned about institutions and institutional forms, and I think we need to look at the wisdom of the Church throughout the years. And so I am hopeful for Christian faith. I'm less so for the institutions we've built, and I'm okay with that, because sometimes we've confused those institutions as either the faith which they're not, or as essential for passing on the faith which they're not. There are inventions that worked in a particular time. What works now? I need to worship with other Christians. I do, or I can't walk and be a faithful disciple of Jesus. I need other people. I need to understand my faith, and I need when called on, to gently explain to people why I think, why I'm a Christian, why I Walk This Way despite all my doubts and all my questions, I continue to be committed to being a disciple of Jesus, who I believe to be God's Son, the Christ.

[John Borthwick]

Thank you, Stuart. I love that. Yeah, just to be in dialog with the doctrinal statements I'm and I'm having a memory issue with living faith. But Living Faith says something about evangelism, and I think it's a beautiful way of putting it, and it's either about food or about fire. I can't exactly remember, but telling, telling someone you found something, and encouraging them to come and see what you found, whether that was, I think it's good.

[Stuart Macdonald]

I think it is too, and it's really good. I also think one of the things that Stephen Hayes was so proud of was having a section of doubt on faith. And I think that was just inspired, spiritually inspired. And the short sentences of Living Faith.

[John Borthwick]

Oh, beautiful document, and it's written in contemporary English, unlike the Westminster Confession of Faith.

[Stuart Macdonald]

So here's a very quick screen. I'm not sure most people can understand the 17th Century when it was right. And I'm a 17th century historian. My PhD is in 17th century. I've spent more time in the 17th century. I'm not sure I get half of what they're saying. It is such a different mindset, and so this is why I think we need to have these things in dialog. But I would even want to say that the main might be something that reflects our culture, not a culture we don't understand, are then going to misread

[John Borthwick]

Well and not to trigger you the same way that I triggered Jamie Robertson, but I'll mention Jamie at this moment because I mentioned you several times in my interview with James, and he got you. He was like, really again, wow. Okay, sure. So let me just give him some credit. In our conversation, we were also just mapping out this, what needs to be in dialog. We were talking a lot about generational stuff. Yeah. So in his book, he talks a lot about Gen X which is near and dear to my heart as a Gen Xer. But even that sort of dialog between generations. How do we understand what each generation in this timeframe that is sitting in the pews or not in the pews? How do we translate the faith for the emerging generations, when, when we've been when we've had a faith either passed on, either taught or caught in our own contextual, generational and as you say, anybody who's not who's starting to think about how we do faith stuff, how we do, how we do education, how we do, how we preach, how we teach, who isn't connecting the dots of what we all experienced with the global pandemic from that started in 2020 you're missing something. Yeah, if you, if you're still working from stuff that's from, you know, pre 2019 It's a new world.

[Stuart Macdonald]

Absolutely, I think Jamie's really spot on there. And again, I would want to say that that's where Christian Smith can be helpful. And again, I want to use it carefully, and it's not the answer. This isn't why it happened. That would be, I agree this might be why it happened in United States. It's not what happened in Canada, because the decline he put so much later than we know what happened in Canada. So not critiquing that wasn't his project, but I think understanding generational experiences and how that shapes questions is absolutely essential.

[John Borthwick]

Well, as you would, I'm sure a firm and your colleagues across Canada would say the same thing, and it's been said many times, but we still are heavily influenced by the elephant that lives just next door to us. You know, contextually for Canadians, if you're if you're referencing stuff that's from the US as a way of how to do this thing in this country, and even in particular parts of this country, without referencing what, is the Canadian way of seeing these things, or the Canadian way of doing these things, or what the culture is in even your small part of Canada you're missing you're going to miss something. It's going to be a misstep, a misalignment. You can try to bring all the powerhouse of resources that comes from the US and try to put it into a Canadian context, but you're not going to have the same experience that you might have read in a book that said, Hey, I did this in my church in Arizona, and it was amazing. It might not be the same experience in Guelph, Ontario or Coburg, Ontario, or Saskatchewan or wherever, right? It will not be.

[Stuart Macdonald]

And Canadian ministers and Canadian church leaders. We now have the resources. We now have the scholars we didn't 40 years ago. To be fair to the Presbyterian Church in Canada, we didn't have what we now have. We didn't have Joel Thiessen's work. We didn't have Sarah Wilkins, Lauren Reimer's work, Brian Clarke and my book, Phyllis Airhart's History of the United Church, we now have resources that map it out. And the one thing that I think every religious sociologist, from Reg Bibby to everyone else, agrees on is Canada is not the United States. That's been the consistent theme. And yet, for church leaders, somehow they haven't heard that.

[John Borthwick]

It's an interesting reality, for sure. So finally, Stuart, what? What do you hope people will take away from reading your book Beyond the passing comment, which I adored, a national office had been duct taped onto the General Assembly. Beyond that comment, and what would you really hope people will take away from your book?

[Stuart Macdonald]

Yeah, it was a fun comment. I fought, no, my editors were great. I was planning to fight to keep that one, but they were great, just fabulous. There were multiple audiences with this book all along. I was always aware of it and Carla Madden, who was my, one of my editors at McGill Queens, was always supportive of this. So one audience is academics, the academic world. This book was written to be accessible. There's not a lot of jargon in it. At the same time, it's still part of a debate how secularization happened, and what I tried to show. I tried to show what I believe happened, that the 1960s are crucial and. And show what it looked like in one particular denomination. So it does have an audience beyond the PCC in the academy for the average person, often Presbyterian, but there'll be others. I wanted to tell a good story. I wanted them to understand the changes that there was a golden age. This is what it looked like, and then it wasn't anymore, and what that looked like, and what that felt like, and some of the key themes that happened, and all of that. So that's another audience. And then for leaders, for clergy and elders and national staff and anyone else in a leadership position in the Presbyterian Church in Canada, or any other Canadian Protestant denomination, all of those things. But I also wanted them to think about and get that we're now in a different reality. So now we understand what happened, and now we're 40 years on. I think we need to respect those who honestly struggled with change earlier on, and honor that. But it's time to do something different, to build the institutions for this culture, which means letting go of the old ones. And so those are the things I hope that those different audiences get from the book.

[John Borthwick]

Well, I certainly found the book to be a treasure and a wonderful trip for some of my own personal nostalgia and sort of pointing at things and going, Hey, I know that person. I remember that place. I've been there those kinds of things. Is there anything that you wished I had asked that I did not?

[Stuart Macdonald]

No, I want to say one quick thing, though the questions have been very helpful. So thanks, John. I also talk about the period from 1925 to 1945 to set up the four themes, which are covered in two chapters each. And I wanted to go at this idea that the Presbyterian Church in Canada never recovered from church union. And you'll see that's an argument in the book. So I really do go back over church union and say some things and actually make the case that no, we actually did recover. We were a thriving church, and that's somehow in the literature, not only in the PCC, but in the broader literature that the Presbyterian Church in Canada really never recovered, didn't have any vibrancy. That's just not true. And I think that was the only other thing I'd add John, is that I think that's also an important thing to think about, is that, yes, we did recover, as difficult as it was, as traumatic as it was, we recovered. Amazing.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah. Really been great to be in conversation with you. Stuart, I'd wonder, as we close, I'd offer a moment of celebratory promotion. I never call it shameless self promotion. I always call it celebratory. Are there new projects that you're working on that listeners should take note of? I mean, is there again your music background? Is it like, will there be some reunion tours playing over the classics, or what's, what's, what's up for Stewart,

[Stuart Macdonald]

Yeah. Where are we on Spinal Tap, the first movie where we're was it mock three whatever they become, a jazz band at the little No. So I'm still discerning, and I don't want to say, I mean, retirement has been great, but there are ongoing responsibilities, which I'm very pleased about, but it's taking a little bit longer than I thought, and that's okay. I've given myself time to figure it out. The one thing that people say, Yo, you should do this, that I want to be absolutely firm. I am not doing. I'm not writing a book that takes the story from 1985 to 2025 someone else can do that. And there's multiple reasons. I just want to say, Nope, I can do something on worship change and the Reformation and in Scotland, I'm fascinated by that. I'm fascinated by more maps. There was so much that got lost in terms of the intense study of the City of Toronto and what church extension looked like, if that be a project. So I'm just trying to figure that what I want to do out I know what I'm not doing, but the question I most want to grapple with is, if this is true, what do we do? And John, you've kind of asked this a couple of times. I do believe it is true, but I think for me, the question is. Like you've just spent all this time on this book. This book took a long time to come together. There's nothing wrong with that. It was just the way it evolved. It was wonderful. But all this is true. What do we do? And so that's the question I really want to grapple with. What have that imagination of what should the church look like, or could the church look like to serve the culture of 2025

[John Borthwick]

I'll be looking for some of your thoughts and answers on that, and so will many of our ministry leaders. Thank you, I'm sure. And also just want to celebrate. I want to celebrate your dedication to the church, to the PCC, to Knox College. We hopefully celebrated you well as you departed. But I just want to take note of that in this opportunity I have, I'm grateful for the fact that you were at the college when I was at the college as a student, and then we got to work together for a brief time. And then hopefully my turning up at the college wasn't an impetus for you to have not a retirement, I'm sure. I'm sure. So, yeah, I want to celebrate that. But also, also want to just take a note from your your commentary throughout, and also just these last few words of I think it's a, it's a great example to ministry leaders today to sort of be a modeling that notion of, you know, taking some time, some time. So you mentioned about pilgrimage and time away or time out, just talking, speaking into ministry leaders to say, you know, sometimes you do need to take some time and to give yourself permission to have time to figure out what's next or what you want to do, or where you want to focus your attention, both within your ministry, but also just in your life and and even as a someone who's recently retired, because I have a lot of colleagues who are already retired as well, and just sort of watching folks as they journey through that journey, and to Give yourself time to think about the things. But I really want to emphasize being very clear on what you're saying yes to and what you're saying no to. And if you don't know your yeses yet, really having a clear sense of your nose as quick as possible, because if you don't have those no's, you're going to get into the space in place where maybe you didn't, you know it just took up your time, and that's not what you want to do. So I really value you saying no to some things and still discerning what are you going to be saying yes to it? Really, really appreciate that.

[Stuart Macdonald]

Stuart, thank you. And Amen, we need to focus on the essentials, not the stuff that takes up our time, and it's so easy.

[John Borthwick]

Guilty as charged, absolutely well. Thank you, Stuart, thank you for joining us on the ministry Forum Podcast. We look forward to probably connecting with you again when you're going to be telling us all the things that we should be doing or could be doing, suggestions, suggestions, imaginations, nudging, curiosities, wonderings. Yeah, it sounds wonderful. It sounds like a kaleidoscope kind of affair, something psychedelic of some kind. Stewart's, Stewart's musings. It'll be awesome, something retro, like as long as

[Stuart Macdonald]

It's so good Paisley. Or, not.

[John Borthwick]

I was visualizing Paisley. That was where my creative, creativity was going. Thank you so much, Stuart, talk to you again soon. Blessings to everyone. Thanks for joining us today on the ministry Forum Podcast. We hope today's episode resonated with you and sparked your curiosity. Remember, you're not alone in your ministry journey. We're at the other end of some form of technology, and our team is committed to working hard to support your ministry every step of the way. If you enjoyed today's episode, tell your friends, your family, your colleagues. Tell Someone, please don't keep us a secret, and of course, please subscribe, rate and leave a review in the places you listen to podcasts, Your feedback helps us reach more ministry leaders just like you, and honestly, it reminds us that we're not alone either, and don't forget to follow us on social media at ministry forum, on all of our channels. You can visit our website@ministryforum.ca for more resources keeping up with upcoming events and ways to connect with our growing community until next time. May God's strength and courage be yours in all that you do. May you be fearless, not reckless, and may you be well in body, mind and spirit, and may you be at peace.