The Christmas That Almost Wasn't: A Conversation with Laura Alary

Laura Alary returns to the podcast and shares the stories behind two new children’s books—one inspired by the Toronto ice storm of 2013 and the other exploring why all living things need darkness. Together, these works invite us to see both the physical and spiritual gifts that come when plans unravel, lights go out, or fear creeps in.

John and Laura reflect on how darkness can hold lessons of resilience, connection, and wonder, especially for children learning to navigate life’s disruptions. It’s an episode that blends storytelling, theology, and everyday experience into a hopeful reminder that even in the dark, God is near.

About Laura Alary

Laura Alary is a storyteller, educator, mother of three, and writer of picture books. Her book All the Faces of Me was named a 2024 Charlotte Zolotow Award Honor Book. She is also the author of Here: The Dot We Call Home, Make Room: A Child's Guide to Lent and Easter, and The Astronomer Who Questioned Everything, among many others. A graduate of Dalhousie University (BA Hons.), Knox College (MDiv) and The University of St. Michael’s College (PhD), Laura now works at Caven Library, Knox College, where (among other things) she curates the Picture Books in Ministry collection.

Additional Resources:

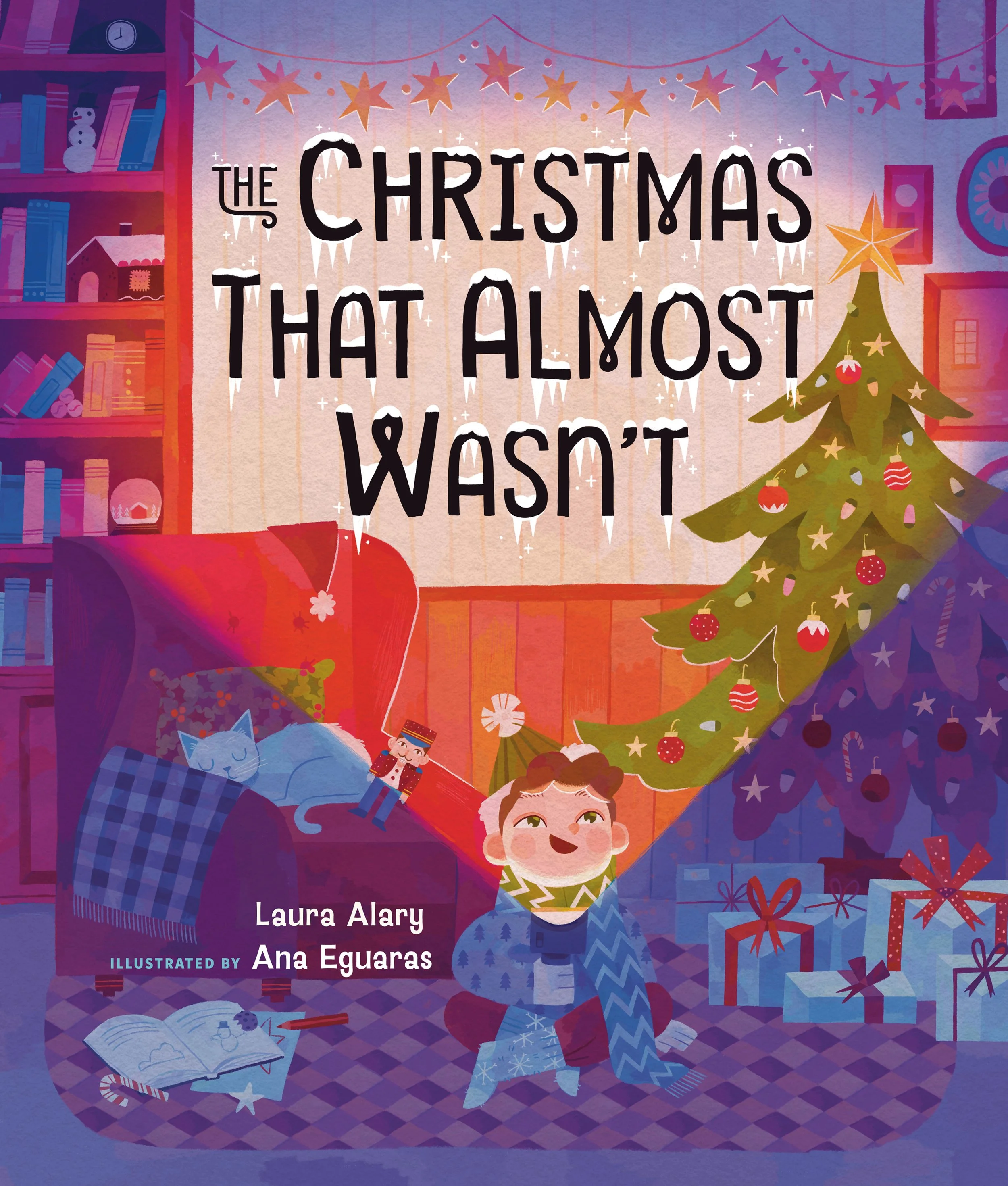

The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t

Celebrating Christmas in the dark and finding joy in the unexpected.

Aidan's city is hit with an ice storm just days before Christmas, causing the electrical grid to go down. All their Christmas plans are ruined! One disappointment piles on another: Grandma and Grandpa cannot travel, the Christmas pageant is canceled, there are no Christmas lights, and it's impossible to cook a Christmas dinner. But Aidan and his dad persevere to bring doughnuts and coffee to neighbors, and then they're invited to a neighborhood Christmas potluck.

As Aidan's mom tells the Christmas story, he realizes that the first Christmas was full of disappointment and unexpected community too. Suddenly Christmas feels special again as Aidan feels connected to the Bible story from long ago, to his grandparents far away, and to his neighbors and family nearby. God is here in the midst of it all.

Sometimes Christmas is not all we hope or expect it to be. The Christmas That Almost Wasn't invites readers to ponder how sometimes, when things are taken away, it brings us closer to the heart of the holy mystery that still draws us into its warmth.

Who Needs the Dark? The Many Ways Living Things Depend on Darkness

A celebration of the dark and all the ways it can heal, comfort, console, and create

How do you feel about the dark? Is it creepy or cozy? Eerie or awesome? The dark doesn’t have to be scary. After all, it’s for sleeping, for growing, for healing, and for changing into something new. Humans depend on the dark for their health and well-being, and so do other living things.

A love letter to darkness, this informational picture book incorporates STEM content to gently encourage readers to look at the dark in new ways. Lyrical, poetic text and soft, striking illustrations make for a delightful read aloud.

Other Books By Laura Alary

Other Books Laura Mention In the Episode:

True Meaning of Crumbfest, David Weale and artist, Dale McNevin

All Creation Waits, Gayle Boss and artist, David G. Klein

Learning to Walk in the Dark, Barbara Brown Taylow

The Long Winter, Laura Ingalls Wilder

Connect and Learn More From Laura Alary

Laura will be a presenter at the Toronto Children's Ministry Conference this Fall

Knox College will be hosting a book launch for Laura on Wednesday October 15 from 5 - 7PM

Follow us on Social:

Transcript

[Introduction]

Welcome to the Ministry Forum Podcast, coming to you from the Center for Lifelong Learning at Knox College, where we connect, encourage, and resource ministry leaders all across Canada as they seek to thrive in their passion to share the gospel.

I am your host, the Reverend John Borthwick, Director of the Center and curator of all that is ministryforum.ca. I absolutely love that I get to do what I get to do, and most of all that I get to share it with all of you. Thanks for taking the time out of your day to give us a listen. Whether you're a seasoned ministry leader or just beginning your journey, this podcast is made with you in mind.

[John Borthwick]

We are back, Ministry Forum community, and today, we begin the Fourth Season of the Ministry Forum Podcast with a returning guest, Laura Alary. Laura is a storyteller, educator, mother of three, and writer of picture books. Her book, All the Faces of Me, was named the Charlotte Zolotow Award Honor Book. She's also the author of Here the Dot We Call Home, one of my favorites for children's times in worship, Make Room: A Child's Guide to Lent and Easter, and The Astronomer Who Questioned Everything, among many others, and we're going to talk about that in a minute. She's a graduate of Dalhousie University with a Bachelor's Honours, Knox College, MDiv, we went to school together for a little bit, and the University of St. Michael's College, PhD. Laura now works at Caven Library at Knox College, where, among other things, she curates the picture books in the Ministry Collection, and where I have the privilege of calling her friend and colleague, and I get to work with her occasionally on things like this.

In our first interview with Laura, back in Season Two of the podcast, we talked to Laura about her calling to be a picture book author and storyteller, and celebrated the ways in which we all answer vocations differently. Today, we're actually going to focus on a couple of specific new releases by Laura. This is a huge year for her. How many books are coming out this year? Laura?

[Laura Alary]

It's a big year. It's five in 2025.

[John Borthwick]

Five in 2025, yeah, way to go.

[Laura Alary]

That's a record for me.

[John Borthwick]

That's awesome. And by the end of the year, the grand total of books that you've released will be?

[Laura Alary]

It will be 20.

[John Borthwick]

Amazing. That's awesome, way to go. Well, it's great to have you on the podcast again, Laura, and we're delighted to have you as a returning guest. Welcome.

[Laura Alary]

Thank you, John. I'm delighted to be here.

[John Borthwick]

Let's start with how it feels to have so many of your creations being released in one year, and for people who don't understand this publishing process, I certainly don't grasp it myself. How does this happen? How does this roll out? Do you have much control over it? What goes on?

[Laura Alary]

Well, first of all, it feels amazing. I said to one of my editors not long ago, because this industry is so competitive, each time I get an acceptance, and the years pass, and eventually the book emerges. It always feels like a small miracle to me, because the odds of that not happening are so great. To have five in one year is huge for me. I'm grateful.

It's also a little bit overwhelming because of the whole publicity part of it. I have something

resembling a spreadsheet to try to help me keep on top of how to promote, what, when, and how. I haven't completely dropped the ball yet, but I'm at my capacity. It's great, and it just happened that I had two books come out on the same day in May, and then these two are coming out within two weeks of one another in September.

As for your question: How much control do I have? None whatsoever. The way it works is that publishers have lists, and by list, I mean the collection, like the particular books that are being published in any given season. Depending on the size of the publisher, there could be a spring list and a fall list. Some publishers have three in a year. There would be a winter one as well. The editorial directors plan those lists out years in advance. It's quite a process. I've only learned about it over the last couple of years. They're trying to balance so many things. In children's publishing, they're trying to balance fiction, nonfiction, different genres, and different ages. How many picture books do we have? How many for middle graders? How many graphic novels? They're trying to figure out: how do these themes relate to one another and the time of year? They are also balancing diverse voices among authors and illustrators. There are just so many variables to take into account.

As an author, all you can do is sit back and let that team do their work. They tell you when your book is coming out. Now, when I sign a contract, usually there's a question that says something like, if your book is going to be published in the spring 2027 season, do you have anything else coming out that might compete with it?

Now, in the case of my two books, one's fiction, one's non-fiction, a Canadian publisher, an American publisher. There are some similarities in theme, but they're not in direct competition with one another, so this is just how it happened. Then, sometimes books get moved around, too; I was supposed to have another one coming out in Spring 2026, and then there were some scheduling issues with the illustrator, and so that's not going to happen. It'll be moved somewhere else. I don't know when it will be published, but try to be patient and wait and see how it all shakes down.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, that's amazing to see how it all pulls together. I'm assuming there's not a lot of interplay between publishers. I would think they're just publishing their own stuff. They have their list, they're thinking about how they're going to roll things out. They're not checking in on other publishers or what other publishers are going to roll out. Or do they have any knowledge of that?

[Laura Alary]

I'm not actually sure. I think that they have enough to do just to kind of handle their own stuff. They do check in with the authors if you're with multiple publishers, because that's where it gets tricky.

[John Borthwick]

Out of curiosity, just because I got to answer a dream, I guess. I was very excited to receive the advanced reader copies of the books you sent me. It was very confidential and had actual comments and notes of: change this, change that. I was like: Wow, so exciting. I've destroyed all copies. Do not fear. One of the things that's fun, especially with picture books, is the illustrations. Do you get a chance to say: I would like to work with this particular illustrator, or is the pairing something that the publishers do?

[Laura Alary]

Well, it's primarily at the discretion of the publisher. It is their choice, their decision. What I've found in recent years, and I don't know whether this has changed in the industry, or whether it's just that I have published enough now that I have sort of built a relationship with some publishers, I am being included in that conversation more, not so much in its initial stages, but sometimes, the editor might come to me when they're at that stage in the process, and say, you know, we're considering X, Y and Z. Do you have a preference, or what do you think about such and such for this book? That doesn't always happen, but sometimes it does, and it's nice to have a little bit of input. I did, in the case of both these books; I did have an opportunity to weigh in on that decision.

[John Borthwick]

That's great. Yeah, and they look beautiful. People are in for a treat when they get to see them. I already got to see them. I'm so excited.

[Laura Alary]

They are very different artistic styles, which is fun, too. One is digital and one is entirely by hand.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah. It's interesting. My daughter's going to the Ontario College of Art and Design, and some of the things you get to see through the students there, I'm always fascinated, especially around picture books and about the different media that people use to make picture books. I remember picking one up in a bookstore and taking a picture and sending it to my daughter and texting her, because she's in textiles. I said: This is a fully illustrated book using textiles.

[Laura Alary]

Yeah, I've seen that. I love paper collage. I follow a number of illustrators who work almost exclusively in paper collage.

[John Borthwick]

It is such an art form and such a devotion to do that kind of thing. It's not a simple thing: we want to create these pieces of art, as well as being a book and a story that's told. It’s absolutely amazing.

Let's dive into what we're going to talk about, a couple of books that are coming out. The first one, which I hope everyone puts under their Christmas tree this year, is actually about Christmas, the Christmas that almost didn't happen. That’s what it's called, The Christmas that Almost Wasn't. For those who are listening, let me give a little description of the book.

Aiden's city is hit with an ice storm just days before Christmas, causing the electrical grid to go down. All their Christmas plans are ruined. One disappointment piles on another. Grandma and Grandpa cannot travel. The Christmas pageant is canceled. There are no Christmas lights, and it's impossible to cook a Christmas dinner, but Aiden and his dad persevere to bring donuts and coffee to neighbors, and then they're invited to a neighborhood Christmas potluck.

As Aiden's mom tells the Christmas story, he realizes that the first Christmas was full of disappointment and unexpected community, too. Suddenly, Christmas feels special again, as Aiden feels connected to the Bible story from long ago, to his grandparents far away, and to his neighbors and family nearby. God is here in the midst of it all. Sometimes Christmas is not what we hope or expect. The Christmas that Almost Wasn't invites readers to ponder how, sometimes, when things are taken away, it brings us closer to the heart of the holy mystery that still draws us into its warmth.

Laura, what's the origin story behind this book? I have a feeling that it could be connected to something that happened in the province of Ontario.

[Laura Alary]

Yes, I figured you would share that memory. There's almost always some story behind the story, and in this case, the connection is more direct than in other books. I wrote this in the aftermath of the ice storm of 2013, which I expect is what you're thinking of. If listeners don't remember that, or were not affected by it, it was a huge winter storm system that hit on the night of the Winter Solstice. I was coming back from leading the longest night service on December 21, and we were hit by a massive quantity of freezing rain. There's been one trade review of this book, and the reviewer refers to a snowstorm, but a snowstorm and an ice storm are not the same thing. Trees were down, power lines were down, and millions of people were without electricity and heat in my neighborhood. Some people lost power for up to two weeks. I think ours was out for about four days, through Christmas Eve.

When I think back to that time, I have this memory of very mixed-up and kind of paradoxical feelings, because there was discomfort and inconvenience; we were cold. My kids were sick of eating porridge after two days. We had 25 candles burning on the dining room table, just to raise the ambient temperature in the room, enough to make it bearable. The pipes in our church froze, burst, and flooded the sanctuary. There was all this worry: Oh, is this going to happen to our house as well? There was a huge mess to clean up in the neighborhood. There was a lot of stress and disappointment, no Christmas Eve service. People couldn’t travel, but it was also exceptionally beautiful.

I remember going out with my kids, and every twig and berry had this coating of ice on it. It was just extraordinary. There was coziness to it. We were wearing our winter clothes inside, bundled up on the couch. I read aloud from Laura Ingalls Wilder's The Long Winter, to try to give us a little bit of perspective on the situation. We went to bed basically when it got dark, and slept so soundly; those natural circadian rhythms took over. There was destruction, but also beauty. There was discomfort, but coziness, busyness, but slowness, all of these apparent opposites coexisting.

I called the original main character Charlie, rather than Aiden, and it was called: Charlie's Mixed-up Christmas. That title didn't stay, but it represented that feeling of all of these opposites being together. On Christmas morning, partly because of a lack of power and partly because of the flood, the local Anglican church opened its doors and invited the Presbyterians to come and join them. I remember sitting in the pew and listening to the priest, the Reverend Steven Kirkegaard. He was preaching on the Incarnation, as you would on Christmas morning, but he was talking about Christ entering into the mess and the vulnerability and the chaos of the world and infusing it with love. It hit me in a different way that year, because we were surrounded by so much chaos and mess. I remember feeling this sense of peace as I was listening to him and seeing this image of seen and unseen worlds coming together. It put me in mind of another Christmas story that I love, called The True Meaning of Crumbfest, by David Weale. He's an author from PEI. I won't go into detail about the story, except to highly recommend it. It's about this little mouse called Eckhart, as in the medieval German mystic Meister Eckhart. Eckhart wants to know the truth about this festival that the mice celebrate every year. It's this mysterious time of abundance when all of a sudden, crumbs appear all over the place, and things that are normally outside come inside. There's this tree that appears in the living room, and to make a long story short, it concludes when Eckhart has this realization that when the inside and the outside come together, that's Crumbfest. The first time I read that, I thought: Wow, that's such a beautiful metaphor for incarnation.

As I was kind of pondering, how can I write about this ice storm experience? I knew that I wanted my story to have this little thread of mystery and wonder running through it. I've tried to include that, and I also wanted to portray the dark in a way that was good and beautiful. That's the origin of this one.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, amazing. I remember that event impacting the Toronto area and further in Eastern Ontario. What I can remember is the blackout of Summer 2003, because I had a wedding scheduled for that Friday in the morning. I remember having to call into the radio station, and then that sort of connection between neighbors, and lots of interesting things happen when everything goes dark.

In the book itself, it does have this feature of light and darkness. Beauty and dismal grumpiness that can happen. There is this sense of the negative. All the negatives are playing into it as you build the story. It spoils all of Aiden's plans. It wreaks havoc in the town, but then he goes and offers some help to his neighbor, and she exclaims that he's the light in the darkness. For Aiden, some of the big Insights come to him because of the dark. We're going to talk about your next book in a second, but can you speak a bit more about this, how these insights come to Aidan because of the dark?

[Laura Alary]

Yes, and it's interesting that you mentioned the neighbor's comment to Aiden: that you are light in the darkness, because that phrase represents the way many of us think about light and darkness, especially during Advent. That's the season when we glorify light and anticipate the coming of the light of the world.

What I was struggling with was acknowledging how we see light and darkness in relation to one another. There is power in that. If you've been stuck in a blackout and you don't have a light source, and then somebody gives you a light, or if you've had a difficult night that feels like it's never going to end, and then the dawn comes - you've experienced this renewed energy. There's something really powerful about light in darkness. I also wanted to emphasize that darkness has its own gift. I was trying to do that in the book as well.

There are two kinds of darkness in The Christmas That Almost Wasn't. There's the physical or natural darkness that results from the blackout, and there's the metaphysical darkness, in the sense of the hard emotions. When the book begins, Aiden experiences both of them, and they are both very unwelcome to him, because they wreck his plans. They spoil everything. I would say that what happens to Aiden is a very gentle, very mild version of the dark night of the soul. He starts out so full of excitement and anticipation, but then events completely beyond his control plunge him into this state of disappointment, confusion, and emptiness, because everything was so full, and all of a sudden, it's gone. There's a kind of obscurity. He doesn't know what's going to happen next. He keeps waiting and hoping the lights are going to go back on, but they don't. He is not happy with the situation, but there's nothing he can do. He's just stuck. But as you mentioned, he's not alone, and so with some prompting and guidance from his family, his dad in particular, and his neighbors, he actually goes into the dark.

He goes out, and I think he learned some things about generosity, empathy, hospitality, and community. These good things he experiences because of the darkness, and then, toward the end, spoiler alert, he has a spiritual experience. It's a very deep connection to the Nativity Story. The reason he has that deep connection is that the hard things in his own experience, he sees reflected in the biblical story. I don't know if you're familiar with Barbara Brown Taylor’s book, Learning to Walk in the Dark. She asks the question: What can you learn in the dark that you couldn't learn in the light? I had that question in the back of my mind as I was shaping this story about Aiden.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, that's amazing, definitely a powerful story, perfect for Christmas time. A powerful story that shows the parallels between a negative impression of darkness as bad and that there are some things that come only from the darkness, or as a part of the darkness, which will lead us into your next book.

I wanted to say, one of the insights, and it parallels your next book and what you've been sharing. Some of the things that you discover when the world goes dark, at least in the blackout experience that we had, we live in the city of Guelph, and during the blackout, our power came back on fairly soon, within a day, and other people's power didn't come on for days in the same city. What we discovered is that if you live in close proximity to the sewage system plant, apparently, it's one of the first things to come online. We've got to keep that system going. Our house happens to be part of that grid, and we lucked out. We wouldn't have said we always felt great about being so close to the sewage plant, but this shows how the dark teaches us these things.

Let's talk about your other book. It also plays on this theme of darkness, but in a very different way. It's called Who Needs the Dark?: The Many Ways Living Things Depend on Darkness. For those of you who are not able to see our podcast, Laura is holding up the book. You'll be able to see it yourself when you go and buy the book for yourself and your family. It's a really neat book. I love, actually, that you have a number of these kinds of books in your almost 20-book repertoire, science-related stuff. You certainly write from a Christian lens, telling Christian stories or sharing stuff from the liturgical year, but I also love these books.

I would imagine there's a translation piece that's still happening, even in the midst of what you might call an educational book, that's sharing some of the concepts you were just talking about around this light and darkness theme. I learned new things about what goes on in the dark from reading it, and I'm grateful for that. It was quite interesting how you've painted that picture, again, around this theme.

Let me describe the book for the listeners, and then let's talk a little bit more about it. The description is: how do you feel about the dark? Is it creepy or cozy, eerie or awesome? The dark doesn't have to be scary, after all, it's for sleeping, for growing, for healing, and for changing into something new. Humans depend on the dark for their health and well-being, and so do other living things. A love letter to darkness. This informational picture board book incorporates STEM content to gently encourage leaders to look at the dark in new ways. Its lyrical, poetic text and soft, striking illustrations make for a delightful read-aloud.

Who Needs the Dark? It is different from the previous book, but it's still on this theme of darkness, and it's coming out this month as well. The podcast will be released in September, and we already talked about the timing wasn't necessarily intentional, but I wonder, are the books connected in some way to each other? Were you writing them at the same time, or is there a connection to this overall theme of darkness for you?

[Laura Alary]

Yes, they both arise from similar kinds of rumination on darkness and what we can learn from

it. The timing is purely coincidental. I have no control over that whatsoever, although it's a fun challenge. Sometimes, when I find out this one's coming out on the 16th of September and this one on the 30th, are there ways that I can help people connect these two books? In this case, I think the answer is yes, because they do work together quite nicely, especially in some contexts. Who Needs the Dark is about natural or physical darkness, and why we need it, which we do. All life on earth has developed within this balance of day and night, darkness and light. We're all adapted to it. We often connect light with life for obvious reasons. I have a book about photosynthesis, too, but we need the dark just as much for many of the reasons that the description names: resting, healing, growing, dreaming, and so on. Who Needs the Dark shows specific ways that darkness is helpful in the life of a child. For example, holding them in the womb before they're born, or supporting sleep, when the body is healing itself, or the mind is picking away at problems and solving them. After it shows the life of a child, it goes on and looks at something similar in nature. The book emphasizes a kind of kinship between humans and the rest of the natural world.

I love to write STEM books, but there's always this thread of philosophy that runs through them. One of the things that the books have in common, other than the obvious theme of darkness, is that they were both dreamed up during Advent. They rose from that soil. I love Advent. It's my favorite season of the liturgical year. I love its symbolism. Over the past 10 years or so, I've been thinking a lot more intentionally about the language we use, the imagery for light and darkness, and the effect of constantly associating darkness with misery, ignorance, evil, and so on. As I was thinking about this, I thought, well, I want to be intentional about exploring how darkness is beneficial to us, and that led me down two paths. One of them was learning about physical darkness and why it's good and necessary, which led me to Who Needs the Dark. The other path was looking at the spiritual or metaphysical darkness and how it is beneficial, which led me in a different direction to The Christmas That Almost Wasn't, but they both came from the same point of origin.

If anybody is interested in using these two books to explore these themes during Advent, I think they work well together. I would start with Who Needs the Dark, because it begins with what's most familiar, the child's own experience of darkness, and then it can prompt them to think about what's good and what's beautiful about it. There's another book that I have to mention, it's by Gayle Boss, called All Creation Waits. There's an original version of it, and then there's a picture book version, and it's outstanding. It connects the Advent themes of waiting and transformation to what's happening to animals as they're getting ready for the dark and cold of winter. There's this beautiful refrain in the book: The dark is not an end, it's a door. It's the way a new beginning comes. It frames darkness in such a positive way. It makes that bridge to Advent, and then to Christmas. From there, you could go very naturally into a book like The Christmas That Almost Wasn't. Sit down with kids and say: Okay, what kind of darkness do we see in this book? How does Aidan experience it, and what are some of the things that he learns from it?

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, as I was reading it, I was thinking of it being helpful in the mind of a child, from being afraid of the dark. In a sense, we're so afraid of the dark for a variety of reasons. As a parent, you could say: Here's why the dark is important for a creature or for something out in the world. This could be an anchor for a child. The dark is helpful because something is going to benefit from it, or needs the dark as a part of its growth or healing, or whatever that might be.

[Laura Alary]

That's part of my hope for that book, that it does exactly that.

[John Borthwick]

Oh, awesome. Yeah, so it sounds like from the two books and from what you shared around the season of Advent. I sense you think it's pretty important to talk to children about the gifts of the dark or the positive aspects of darkness. Did you want to share more about why you think that's important? Is it an answer to something that we see out in the world or culture today? I'll leave it to you to provide a thought on that.

[Laura Alary]

Yes, I do think it is important to talk and think and wonder with children about the gifts of darkness. In a nutshell, I think this is because how we handle our fear of the dark has consequences. I'm going to start with natural or physical darkness. Lots of kids are scared of the dark, and some adults, too. I know I was when I was a child, and I had the little sunflower night light in my room. Part of that is a very natural response to the unknown. We're wired to be cautious of potential risks or danger, especially when we don't see well, but sometimes our imaginations create monsters where there aren't any, and then we exaggerate the risk. It's not just kids who do that. You. How do we respond when a child is afraid of the dark? Well, we add more light, right? You stick the night light in the outlet, you leave the hall light on, and maybe add fancy lighting in your garden. If it's a public space, we add more security. As human beings, more and brighter light makes us feel safe, even if it objectively doesn't do that. It makes us feel safer, but it also comes at a cost.

We disturb ecosystems that depend on this balance between light and dark. As I was reading, I was affected by realizing what a huge problem light pollution has become, leading to the extinction of whole species, pollinators, especially, and that becomes an enormous problem for everybody in the food web. We damage human health by interfering with our natural sleep cycles, circadian rhythms. We don't necessarily give our children a chance to befriend the dark and see what's beautiful about it. The other thing is, if we're always pushing back the dark, we're always using light to get rid of it. We never practice being brave, or kind of facing some of the things that scare us.

I was remembering as a kid, being terrified to go down into the basement, and my parents would give me these little errands that involved going to the basement. I don't know if it was intentional, but sometimes I think maybe they made me do that, so I could practice going downstairs, and I knew no harm was going to come to me. They were letting me practice facing those fears a little bit at a time and building up my courage. If we never do that, that's not beneficial.

[John Borthwick]

It's interesting, the impact of having lights on all the time, like in the city of Toronto, some of the high-rise buildings and business offices had campaigns where they've tried to turn off the lights in those spaces because of the impact it has on birds and other kinds of things. In Aiden's story, when nighttime comes, it’s night and everyone stops working. If you've been in places where it was so dark that when you opened your eyes, it was still dark. Whereas in your house, if it's all dark, there's enough ambient bits of light, you can look outside, and there's probably a street light somewhere. I’m fascinated by homes these days. I don't know what they're thinking, no offense to anyone who has a home like this, but homes that are putting lights all around the home, and they're on all night long. It's like, wow. Doesn't the light come into the house in some way? Our sense of more light is what is needed, as opposed to building this relationship with the darkness.

[Laura Alary]

There's an organization called Dark Sky International, and I've been following them and exploring their website, and they've got some helpful stuff. Not only on the importance of darkness and the risks all of that light poses, even in our neighborhoods, but they've also got suggestions for pollinator-friendly lighting. It's not as simple as saying: Oh, let's get rid of all artificial light. Obviously, that's not going to happen, but there's better and worse lighting. There are things that we can do, too, but part of it is awareness and just realizing: Do I really need to spotlight or floodlight my house all night long? Why? And then what impact is that having on other things beyond me and my family?

That was the physical darkness, and then the metaphysical darkness follows a similar path. For Aiden in the story, every darkness is a metaphor for this sense of security, not knowing what's going to happen next, and the sense of powerlessness. Everything's gone haywire, and there's absolutely nothing he can do about it. He wants the lights to go back on, but he can't make them go back on. He can't get rid of the dark. That's how a lot of us feel at one time or another when unwelcome events come, and we experience hard emotions in response.

Well, what do we do? We try to turn the lights on. I think certain strands of Christianity are particularly good at that. There's kind of a relentless positivity that really isn't helpful in the long run. I was remembering as a child, I was probably seven or eight years old, and I went to Vacation Bible School at a church of a different denomination, and I was already a bit off going in because I didn't really know anybody. I was quite shy, and there was a high energy level that was overwhelming for me, but what made it worse was that at the end of every day, they would give prizes to the kids who smiled the most.

[John Borthwick]

Jesus loves your smiles.

[Laura Alary]

That's right. You know, if you've got Jesus in your heart, you're going to be happy all the time. What I took away from that was the sense that the hard feelings I was having were not welcome. There was no place for those. I think that on a larger scale, if with children, we're always associating the presence of God with what's bright and cheerful and happy, what on earth does that say to them when that is not how they're feeling and when circumstances are not cheerful and bright? As a parent, of course, I want my children to be happy, but it's like that basement thing, right? I know that as human beings alive in this world, we will not be happy all the time; it's not possible. I have always wanted them, not just to avoid the hard feelings, but to actually build up the courage to explore and express them. To sit with them, and say: How am I feeling right now? Why am I feeling this way? To build up the patience and the courage that we all need as people living in this world to stay with things that we find difficult and discover that there are things to be learned, or that there are gifts hidden in there. I say that with caution, because I'm not saying: Oh, terrible things happen to teach us lessons. That's not the message that I'm trying to send. What I'm saying is that it is possible to practice patience and courage, and openness to the transformations that may come out of the dark.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, those are amazing life lessons for sure, for children of all ages, from zero to 115. Some of us need to realize that sometimes life happens the way it does and not what we want to happen, so that we can learn things, or we want this to happen to us, so we can grow. How do I make meaning in the midst of this? How do I find a way forward when the power goes out because of an ice storm, or when plans are ruined? I've always been grounded by Psalm 23, which talks about going through the valleys. It's not saying: If you were a cool God, why don't you make a bridge over the valley, so I don't have to go through it? The Psalm says: I will go with you.

[Laura Alary]

Yes, through the valley, it's that presence in the dark.

[John Borthwick]

That can come in the embodiment of, as you've shared with us, the story around Christmas. You know that can come through connectivity with other people or having a sense of the bigger story that's going on around you. As human beings, who are residents of this planet, that includes a lot more than just us, our connectivity to the Earth itself and to created things can really deepen our appreciation of how something happening to us, or our desire to fix something that's happening to us, could impact other things. I think those are the wider stories you're telling within a children's book that can really be meaningful, both for parents or grandparents, or whoever wants to share this story with a child. Yeah, amazing stuff.

Laura, anything I haven't asked that you wanted to share? Get in there.

[Laura Alary]

I have three little tidbits that I'd like to share. The first tidbit is that for anyone who is interested, The Christmas That Almost Wasn't has a free discussion and activity guide that I've written to go with it. There are a couple of pages of back matter at the back of the book that have some suggestions for playing with light and darkness, and the activity guide expands on that. There's a bit about lament, the longest night, and so on. That's available through the publisher Beaming Books. If you go to their website to the product page, there’s a free PDF you can download. Both books are the core of a workshop that I'm going to be leading at the Toronto Children's Ministry Conference on November 1. I believe it's a Saturday. If you are in the GTA or beyond, registration is open for that conference. It would be great to see you there. There is going to be a launch for both books at Knox College on Wednesday, October 15, from 5-7 PM. We're going to be celebrating the dark.

[John Borthwick]

Way to go. Laura, I know that self-promotion isn't really your thing, but you did a fantastic job. Your publisher will be pleased.

Thanks, honestly, I think the kinds of things you're putting out into the world, your heart for it, your passion for it, the spirit, the creativity, the things that happen. I think this is beautiful that you get a chance to put this into the mix. In a sense, we talked about this in the previous podcast: the word count is limited in these books, and I know that you have the capacity to write a PhD thesis, a hundred thousand words, but the fact that you're able to package it in this tiny piece, but yet it can be so meaningful, I think, is a beautiful gift to the world. I hope people will reach out to get your books and to connect with you in the ways that you've already offered. I really appreciate it that at the end of the book, because you don't always see that in children's picture books, you provide back matter, so readers can go even deeper into the thought-provoking topics.

[Laura Alary]

It's in there to help, especially teachers, parents, caregivers, to say: besides reading the book, where else can we take this conversation? Or in some cases, what activities can we do to reinforce these lessons? In Who Needs the Dark, there are a couple of little experiments that kids can do. There are activities in the back matter of The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t.

[John Borthwick]

Yeah, both books have additional resources. I thought that was amazing and really helpful. Laura, we appreciate you so much. We are so glad that you have joined us again on the podcast. You are launching our Fourth Season, so we're grateful for that. This episode is coming out the week that these books are being released, so folks can purchase or pre-order them.

I am glad you highlighted the Toronto Children's Ministry Conference. We highlighted that last year, and you were a presenter there last year as well. People can learn more about the event at ministryforum.ca, and our events calendar will certainly be celebrating that as well.

Laura, it's been so great to have you again as a guest on the podcast. I appreciate you and the work that you do and the ministry that you have created through these books. We are grateful that we're going to get to celebrate a book launch with you next month. Thank you for joining me.

[Laura Alary]

It's been a pleasure, John, thank you for having me.

[John Borthwick]

Thanks for joining us today on the Ministry Forum Podcast. We hope today's episode resonated with you and sparked your curiosity. Remember, you're not alone in your ministry journey. We're at the other end of some form of technology, and our team is committed to working hard to support your ministry every step of the way. If you enjoyed today's episode, tell your friends, your family, your colleagues. Tell Someone, please don't keep us a secret, and of course, please subscribe, rate, and leave a review in the places you listen to podcasts. Your feedback helps us reach more ministry leaders just like you. And honestly, it reminds us that we're not alone either. Don't forget to follow us on social media @ministryforum, on all of our channels. You can visit our website ministryforum.ca for more resources, keep up with upcoming events, and ways to connect with our growing community. Until next time, may God's strength and courage be yours in all that you do. May you be fearless, not reckless. May you be well in body, mind, and spirit, and may you be that peace.